Sydney Morning Herald

by Matt Buchanan

As the front man for the Whitlams, he played the roughest pubs for years without much success, but now Tim Freedman is doing very nicely indeed – and he got there without the help of any big record labels. MATT BUCHANAN reports.

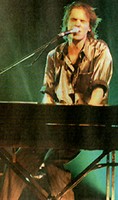

“ARE there any intravenous drug users here tonight?” calls out the Whitlams’ front man, Tim Freedman. It’s their third night back in Sydney and second night at the Metro after a 32-date national tour. It’s packed. As a young girl behind me shrieks “No, Tim, no”, a likely reprobate in the front row gingerly puts his hand up. Freedman, all vulpine charm in a shimmering silver shirt, peers over his keyboard and acknowledges the guilty party. Beaming, he looks back out into the crowd.

“ARE there any intravenous drug users here tonight?” calls out the Whitlams’ front man, Tim Freedman. It’s their third night back in Sydney and second night at the Metro after a 32-date national tour. It’s packed. As a young girl behind me shrieks “No, Tim, no”, a likely reprobate in the front row gingerly puts his hand up. Freedman, all vulpine charm in a shimmering silver shirt, peers over his keyboard and acknowledges the guilty party. Beaming, he looks back out into the crowd.

“You really know you’ve made it,” he declares, “when you’re playing to rooms where only one in one thousand is an intravenous drug user.” He then spreads his long arms wide in an attitude of ironic embrace and cries out “The heartland “.

And the Whitlams have made it. In spades and against the odds.

As little as a year ago there was a good chance the seedy pubs and sparsely attended rock venues that had been their lifeblood for five years would never see them again. More than a year had passed since their co-founder, the songwriter and guitarist Stevie Plunder, had committed suicide, and their most recent single, You Sound Like Louis Burdett, had stiffed. But the Whitlams – who by this stage were no more than its other founder, piano man Freedman, and a clutch of musician pals – persevered courtesy of a small cash injection from the independent recording label Phantom Records, and their third album, Eternal Nightcap, was midwifed into being. But this time the record didn’t fail. It went, as they say, off. And it was out of the garage and into the showroom.

Eternal Nightcap has sold more than 100,000 CDs in the eight months since its release, largely helped along by touring on the back of the daffy but tender ballad No Aphrodisiac, the surprise No 1 single in Triple J’s annual listeners’ top 100 poll. And if Eternal Nightcap achieves double platinum sales (140,000), as expected, it will eclipse the legendary Skyhooks’ Living in the 70s as the largest-selling independent record in Australian rock history.

This is the music industry equivalent of winning the Melbourne Grand Prix on your home-made go-kart. And a lot of people were delighted to see the Whitlams take the chequered flag.

“I think people are pretty amazed by their success,” says Elissa Blake, acting editor of Rolling Stone. “They’ve long been thought of as a quality band, but they had an underground following. In the industry, people really are very interested in what they’ll do next. Now they’ll want some help from a bigger company to help promote their work overseas. They can conquer Australia all by themselves, they’ve shown that.”

So how did they do it? Was it radio support? Great songwriting? A slowly seeded market out there that refused to bloom until nourished by the strains of No Aphrodisiac?

“I think it’s true that Triple J helped them a lot, but really any band can have a freaky hit, whether indie or major,” Blake says. “With No Aphrodisiac they’ve had a big fat, freaky hit. But I think it’s all in the lyrics: the whole line, `there’s no aphrodisiac like loneliness’. It struck a chord with a lot of people. Plus they’re touring like mad things: every little country town or RSL, they’re there. But no amount of touring and high rotation is going to help if the songs are no good.”

What is truly gripping about the Whitlams’ phenomenal success is that as an independent band they cut out the middlemen of the music business: the big record companies.

The Whitlams are signed to a wholly independent label (Black Yak) and they have independent distribution (MDS). Consequently they have not had the benefit of a large company throwing huge advances at them. But, by the same token, they’ve had no other party swallowing up a percentage of the revenue either. It all streams back directly to Black Yak, which Freedman co-owns with the Whitlams’ manager, Kim Thomas and Phantom Records’ Sebastian Chase.

And as the Whitlams are the sole act signed to Black Yak, to say the Whitlams have made it is also to say that Tim Freedman has got it made.

For this raffish, inner-city pub-rock piano journeyman who employs his band is, in a very real sense, signed to himself. And it follows that if a big label does sign up the Whitlams it will be signing up Freedman’s enterprise.

“Yeah. I’m signing,” Freedman confirms, leaning his rangy frame back into his garden chair in the courtyard of his home of 10 years in Newtown. The angular Freedman is in full possession of an unholy trinity of charisma: talent, wit and looks. That the charisma has a whiff of sulphur is merely part of the appeal.

“We’ve done very nicely these last few months,” he continues. “Usually the record company makes more money than the band, but because we’re the record company and the band, we’re probably making three to four times as much as anyone else on the charts. When we sell 100,000 we make as much money as if Wendy Matthews sold, say, 400,000.

How does the current line-up – guitarist and singer Ben Fink, ex-Warumpi Band drummer Bill Heckenburg and ex-Peril bass player Cottco Lovett – figure in Freedman’s grand scheme?

“They’ve got plenty of input musically,” says Freedman. “I wouldn’t hire them unless I respected their musicianship and personalities, so it operates like a team, but I have the casting vote. They get a cut of the gross and the grosses have been good. But at this stage it’s my vehicle. They’ll probably be interested to read this article. You probably know more about the record deal than they do.”

The putative deal, with the US giant Warner Bros, is expected to be favourably concluded at the end of this month. Favourably because besides raking in extra cash per CD sale, the Whitlams’ DIY approach has granted Freedman a powerful edge: bargaining power and the ability to make a big label sweat for a change.

“When they go in to negotiate they are in a stronger position,” says Mark Callaghan, artists and repertoire manager of Festival Records and ex-singer/songwriter of the ’80s Oz rock stalwarts Gangajang.

“Because they have an existing fan base of, say, 100,000, the risk is less for the record company. Even if they sell half as many next time, that’s still a hell of a lot of records. They’ll get better advances, some hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is their own money, because it’s only recoupable in royalties,” Callaghan says. “And they’ll get more resources because the record company knows they’ll recoup that money. They’ll get better percentage points as well. We all think it’s great to see.”

Freedman is understandably jubilant about being in such a strong position.

“As it’s not signed yet, all I’ll say is, if we sign this deal, it’ll be a tremendous example of a fair record deal, and I haven’t seen many of those over the years,” he says. “Usually in negotiations with a major company the band is in a position of weakness. But we are going in to them with a platinum record already in the bag. If they’re going to become partners in our already successful business we’re talking good advances, we’re talking good percentage points and we’re talking about having confidence in a company with good overseas organisation.” FOR those unfamiliar with the Whitlams it is possible that Tim Freedman may have registered in the popular psyche as something other than a tousled song and dance man or successful small businessman. In newspaper reports he was the “rock star” friend of Jennifer Smith, the young Sydney journalist bashed to death only metres from his door early one morning in January this year.

“I don’t think they put those headlines in the Telegraph to help sell my CD,” Freedman says, referring to insinuations that he was the focus of an obsessive woman.

“It was all a little taste of how celebrity can be extremely unpleasant. But I was proud that everyone around me just shut up and wouldn’t talk to them. The Daily Telegraph sent people to Newcastle and Canberra. They couldn’t even get in the show. They just sat downstairs. They couldn’t get a comment, a photo, anything.”

According to Freedman, Smith was an old colleague from university possessed of writerly aspirations who overly romanticised their relationship, using it “as a muse of sorts”.

“In the interests of art, I think, she enjoyed the performance and trappings of unrequited love, or the failed love affair. But it wasn’t the centre of her life. It was mere coincidence and horrible luck that she came to knock on my door that night. Suddenly what was a small part of her life became what defined her in death.”

Violent and tragic death is something Freedman has had to contend with more than most in the past few years. Indeed, he is perhaps best known as the remaining half of the original Whitlams: a possibly corrigible rake, a pianist and singer who decided to keep knuckling away at the ivories and continue the band after Plunder was found at the bottom of Wentworth Falls on Australia Day 1996, almost four years to the day since he and Freedman had drunkenly decided to form the band at the first Big Day Out in 1992.

“He’d given up smoking about three weeks before,” Freedman says with a wry smile. “That was the main reason [he jumped]. He used to smoke about two packets of reds a day. He just gave up [smoking]. He got very depressed one day and took the train up to Wentworth Falls. I think he probably jumped in a bit of an emotional state.”

Could the period following Plunder’s death be responsible for the emotional freight and ultimate success of Eternal Nightcap ? The album was put together over 13 months by a whole community of Freedman’s muso mates, including organ luminary Chris Abrahams, and showcases a musical sensibility whose compass takes in anything from vaudeville to the tenderest melancholy. The three very powerful “Charlie” songs appear to refer to Plunder – the songs’ narrator agonising over a close friend’s lack of fulfilment and slide into dissolution.

“I was surprised as much as anyone that Eternal Nightcap did as well as it did, because I had just planned it to be a clearing of the decks,” Freedman responds, declaring that the album was born less of a specific pain than a general melancholy.

“I was just getting all of these highly wrought songs out of my system. I’ve got piles of e-mail and letters which tell me that people could connect with it emotionally, I guess, because it’s about friendship. And that’s the one thing that kids and 20- to 30-year-olds all think about at night. What’s going on with their friends, and people that are screwing up. So the songs were born of a certain melancholy. But that’s a very potent thing because really it’s the second best feeling you can have after laughter.”

It seems paradoxical but predictable that Freedman’s relationship with Plunder, which so clearly inspired some of the very songs the fans adore, should also inspire gossip. But rumours and speculation don’t seem to irk him overly.

“I heard a tremendous rumour a little while ago that Stevie and I were homosexual lovers and that we’d had a fight. I rolled around on the floor for a good few hours about that one. It’s amazing the rumour mill and what goes around. But it’s water off a duck’s back. Bring on the next one,” he says, laughing.

That Tim Freedman is unapologetically ambitious is not surprising when you see it is born of a runs-on-the-board conviction rather than hubris.

“We always had this dream that you didn’t have to sign away your life and you didn’t have to get 15 per cent of wholesale. That if the major labels didn’t agree to our terms we were willing to walk out of the room and do it ourselves at any moment. It’s probably one of the reasons we got ourselves a pleasant deal. And they know it.”

Does he ever worry about seeing it all sink out of sight, disappearing as swiftly as it seemed to arrive?

“The band’s work ethic is strong enough and professional enough to handle it,” he replies, drawing on a cigarette. “I don’t think we’re going to be like little flares that go off and then sink down again. It takes just as long to get to the bottom as it does to get to the top. So I’ve got a good seven years, even if the diminishment of our success starts today.”

Whether they’re selling deeply compassionate ballads, quirky love songs, or, as it turns out, launching the ALP’s contemporary music policy later this month, the Whitlams are organised. Have been for ages. Like a reservoir waiting for a deluge, they just didn’t have that much to do. But they were prepared for any eventuality. Even success.