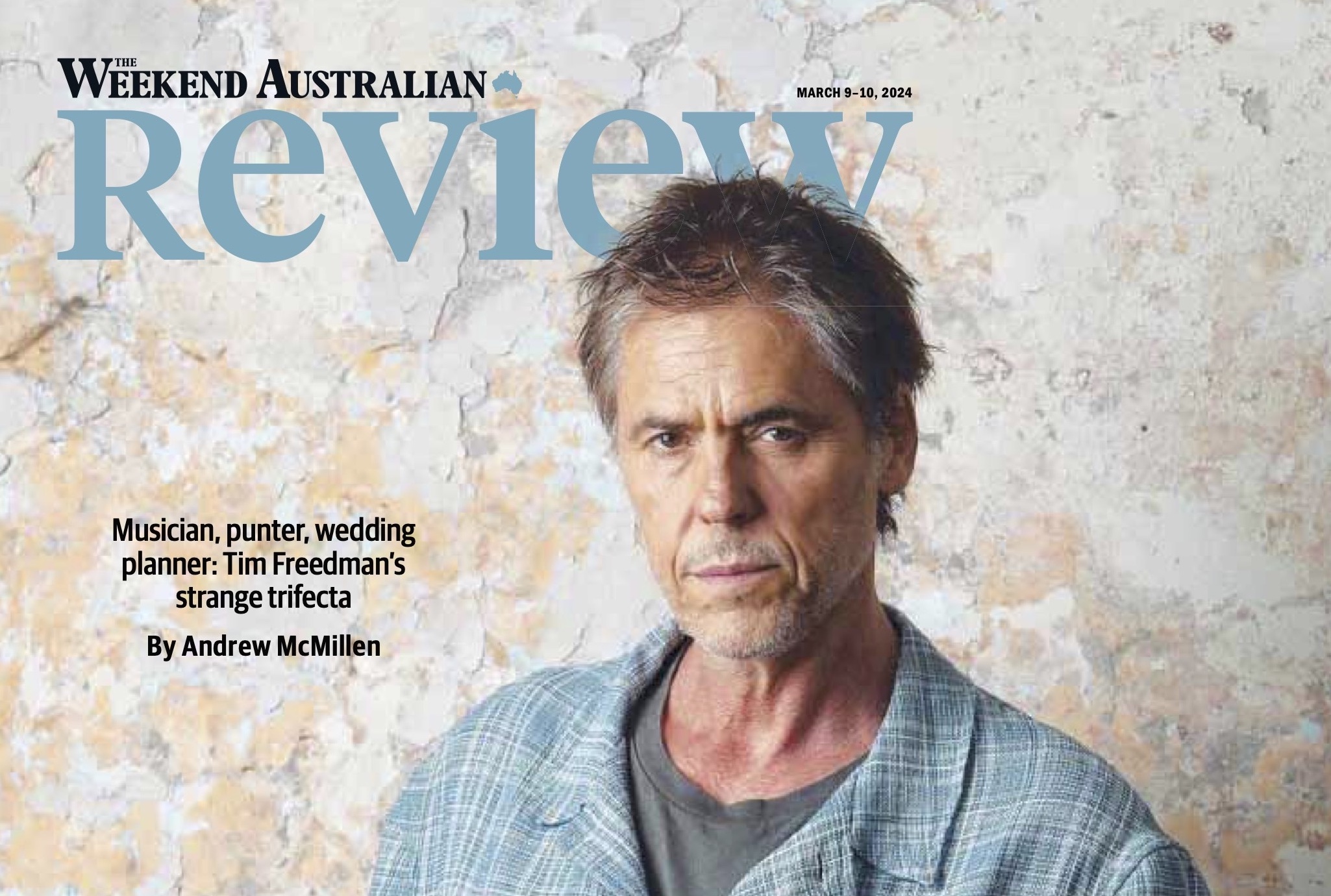

The Whitlams frontman Tim Freedman is taking a punt on a new sound, writes ANDREW McMILLEN

When Tim Freedman opens the front door to his holiday home, we’re invited into a space usually reserved for noisy celebrations of love and commitment. On this warm afternoon in late February, though, there’s no wedding taking place. Instead it’s a peaceful scene situated near bustling Byron Bay, and far from a full house: once Review arrives, its two occupants are still outnumbered by the local wildlife that calls the surrounding rainforest home.

Freedman’s place is called Barefoot at Broken Head, a Balinese-style sprawl of five bedrooms connected by decks and walkways, on a private property. It’s a gorgeous, exclusive and unusual spot for one of the nation’s most celebrated singer-songwriters to call his own, but inside, one of the only clues to the owner’s deep connection to popular music lies in a frame hung in the honeymoon suite: a curious George Hughes artwork that depicts a shirtless boy practising piano while wearing flippers and a scuba mask.

Oh, and there’s an upright piano in the central meeting area, from which its owner has removed the instrument’s front panel to expose the inner mechanics of the black Yamaha U3.

As the pianist and frontman of indie rock act The Whitlams, Freedman’s songs first found a wide audience decades ago, most notably in 1998, when the band’s signature song No Aphrodisiac achieved the rare double of topping the Triple J Hottest 100 poll and winning song of the year at the ARIA Awards.

Its striking opening couplet remains one of the most memorable to have impressed itself upon the national psyche:

A letter to you on a cassette

‘Cause we don’t write anymore

Gotta make it up quickly

There’s people asleep on the second floor …

Across seven albums, a range of line-up changes and an extended hiatus, Freedman is the last original Whitlam standing, and he’s welcomed Review to northern NSW to discuss his left turn into country music tones and Americana textures.

It’s both a creative reconfiguration and a calculated extension of his past, and the new outfit demanded a new name: The Whitlams Black Stump, whose forthcoming debut – which can also be considered the long-running band’s eighth album – is titled Kookaburra. It’s so named because of the love Freedman has for the sound made by the native birds, plenty of whom live nearby the beachside premises he’s owned for the past 15 years.

In 2009, he took a punt on buying a property that stretched his budget, even as his life took a detour into the opaque world of professional gambling. One evening, three of Freedman’s vocations – musician, gambler and “accidental wedding planner” – converged at this spot. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Presently, Freedman is leading Review out the back gate and stepping down a sandy path through a section of bush that leads toward the sound of crashing waves. He’s telling the unlikely story of how he ended up owning this home away from home, having been based in the inner-city Sydney suburb of Newtown for the past 35 years.

Previously known as the Broken Head Leisure Resort and owned by the Taylor family, it was discovered by Freedman around the time The Whitlams first played at the Railway Friendly Bar in Byron Bay, around 1994.

“I fell in love with it,” he says, closing the gate behind us. “I was known as ‘The fella in cabin five’ – that’s how often I came up. It was $80 a night, and whenever I needed to get out of the city and slow down, I’d come up here with a book and a surfboard, and rent cabin five for a few weeks. It was my magical place.”

So it remained for more than a decade, and when the Taylors opted to sell the property in 2007, the developers allowed Freedman to stay in his favourite place. Most of the houses had been sold off the plan for large profits, and Freedman watched them go up around him. But in 2008 when investors reneged on their contracts, the desperate developer thought of the bloke who loved resting his head in cabin five.

“He rings up and says, ‘I’ve got the bargain of the century for you,’” recalls Freedman. “I was such an unsophisticated investor that I just had money in the bank, no shares; so I bought it. And then, of course, the GFC churned through the economy, and the price went down, down, down, and I sat in the middle of this complex – with all the other houses in the black – wondering what the hell I’d done.”

We step out on to the all-but-deserted beach, mimicking a journey he’s made countless times – often barefoot, with surfboard in hand before paddling out to the right-hander that breaks out front. “You can see why it’s such a romantic proposition, buying this house on the spot where I used to come for $80 a night,” he says.

Nowadays, you won’t find many rooms at that sort of rate anywhere in the Byron Shire. Rental costs for Freedman’s place, which he bought for $2.8m, range between $8200 and $18,000 per week.

The investment kept him busy, and property planning issues largely kept him away from playing or recording music, other than a solo debut titled Australian Idle, which Sony released in 2011.

“In the time it took me to build this business, I could have written three albums,” he reflects. “But that was just one of the reasons I went quiet. I’m glad I did, because I felt a lot healthier at the end of that decade, anyway.”

With the benefit of 15 years’ hindsight, the story behind setting up Barefoot at Broken Head is one Freedman can tell with a smile, and an occasional grimace. “It’s not a bad problem to have, to be able to spend time somewhere like this – it’s just been not without its vicissitudes,” he says evenly, as we head back toward the house.

“Half the time that I’ve owned this, it was bad luck that brought me here, falling in love with the romantic notion of living in my favourite place in the world. The second half of the time – as the kookaburras wake me up at 6am and I go for a surf – it feels suddenly like it was all worth it.”

Freedman, 59, didn’t set out to become a serious gambler. For most of his life, his only experience in the world of wagering was enjoying a social game of poker with friends, while despairing from afar at the scourge of poker machines as they spread from NSW clubs to pubs, which he famously captured in a 1999 song titled Blow Up the Pokies.

“I wrote that song when I noticed my third friend in a row ruining his finances and mental health because of the pokies’ sudden ubiquity,” he says. “It’s a particular story, but it’s a protest against the industrial gambling complex in which the government is addicted to the revenue stream, which is bad for its population. It remains a very sad blight on Australian society.”

How did the friends who inspired the song respond to Blow Up the Pokies? “I never asked if they’d heard it – and tragically, my former bandmate and co-founding Whitlam, Andy Lewis, passed away before it was released as a single,” Freedman replies.

Over dinner at a restaurant near central Byron Bay called Light Years, the artist is choosing his words carefully as he recalls his time on the periphery of the horse racing industry, in which he “fooled around” from about 2011 to 2017. In his mind, there’s an important distinction to be made at the outset: “Pokies are a system in which the bettor always loses, whereas the horses – in this instance – were not.”

He entered this world by accident, when he got an offer on a Saturday afternoon to play a 40th birthday party on a Monday night in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. “I thought, ‘That’s strange: two days’ notice, nice fee, go and sing some songs …’,” he says. “So I turned up, did my gig, and I said to the birthday boy’s wife, ‘Why is everyone here on a Monday night? Are you all in the restaurant game?’ She said, ‘Oh, no – we’re professional gamblers.’ And my ears pricked up, mainly because I like people bucking the system.”

The birthday boy was a Whitlams fan, and Freedman offered a work exchange program: his new friend would come backstage at the band’s next show, and Freedman got to watch how this highly successful gambler made a living from wagering on horses based on vast amounts of data.

The experience was akin to walking down a main street, before one day being beckoned into an unseen alleyway, down which surprising treasure was hidden away, waiting to be extracted from what the pros call “the corporates”: Australia’s biggest gambling companies.

“It suited me, because I didn’t want to go on the road as much; my daughter was young,” says Freedman. “You had to be very or- ganised and disciplined. I viewed it as the first time I’d had a job, because music was a passion I monetised; I still think of it that way. And gambling was fun in another way, because going on the road and singing to people is an adrenaline rush very similar to yelling ‘Go!’ at the television when you’ve got $5000 on a favourite.”

Over fish curry and firecracker chicken at Light Years, some- thing resembling “peak Byron” surrounds us, from the earthy tones of the restaurant and its casually dressed diners to the five glowed-up young women sitting at a nearby table, who look as though they’re holding a board meeting for the shire’s prolifer- ation of yoga studios. When a shirtless, tattooed behemoth of a bloke strolls by while carrying two tiny Pekingese dogs in his enor- mous arms, Freedman summarises the scene thus: “The clueless self-approval involved here has to be drug-induced.”

The singer-songwriter has fond memories of his years spent down that wagering alleyway. “I met some great people, and had a really good time: it was a lucrative, amusing and enjoyable side- line,” he says. “I felt very lucky to be trusted in that environment. I didn’t have an ambition to become a punter; it just fell in my lap.”

The best day he ever had involved a $300,000 windfall.

“That was the best multi [bet] by far, and by far the biggest win,” he says. “That figure is true, but you’ve got to understand that you almost rely on one of those a year to cover your bad days. And if you’re willing to lose $30,000 in a day, you’re doing that because one weekend, you’ll pick seven winners out of 11, and have framed them in a way that brings in that much money.”

So why did he stop? That cat-and-mouse game between professionals and corporates, and their escalating arms race of data and technology, was making it increasingly hard to place bets and col-lect. “It was like being a lobster in a pot of boiling water,” says

Freedman. “They were just getting better at their risk analysis. Picking the winner’s just a third of it, and I was involved in the other two thirds.”

Naturally enough, the songwriter later folded a few of these key details into the final verse of (You’re Making Me Feel Like I’m) 50 Again, a single that appeared on The Whitlams’

2022 album Sancho, and also on the newly released Kookaburra:

I was betting with tomorrow’s paper

I really had it made

But now I hear you gotta win three times:

Pick the horse, get on and then get paid

“Anyone in the gambling industry knows that anyone who’s good at it needs to be creative in how they get bets on, because the risk management driving the corpo- rates’ culture is so stringent now that

if you’re good, you might last 16 min- utes before you’re banned,” he says. “And all you guys that are still allowed to put $5000 on? That’s because you are losers, and they know it. Simple as that.”

As for the day a few years ago when three of his worlds collided – music, gambling and owning a wedding venue – it’s a yarn that Freedman begins telling when we’re back lounging at the house, facing the piano.

“It was a nice boutique wedding for 24 people, including a lovely couple,” he says. “The bride said I was allowed to sit in the honeymoon suite, away from the guests and follow the races on my computer and watch the plasma. So I sat on the bed and followed the race meetings, from race one to six.

“The gentlemen that were attending the wedding would come in to go to the bathroom and ask what I was doing, and how much I had on,” he says.

By race six, Freedman looked around and realised half the male guests were sitting on the bed with him, gambling apps open, following his bets and cheering along. The bride was understanding, but would occasionally chastise the blokes to come back out for the speeches. It was about this point in the wedding – there’s always a point, he says, roughly four or five drinks in – when a bridesmaid lost her inhibitions enough to come out with it by asking him: “You’re that bloke from The Whitlams, aren’t you?”

What followed was the usual request to sing a few songs, which he would usually decline. But he was in high spirits. If one of three horses in the last race got up, and he won the quadrella, he’d do it.

“And well, in race eight, it came down the outside and won,” he says, grinning.

“All the blokes cheered and dragged this heavy piano out and put it in the middle of the courtyard. I sat there and gave them 20 minutes of the ‘greatest hits’, and we had a fine old time. It was a strange wedding, coloured by a strange venue owner.”

What was the setlist? “Oh, it had to be the novelty side of The Whitlams: I Make Hamburgers, You Sound Like Louis Burdett, Gough, Thank You (For Loving Me At My Worst), I Will Not Go Quietly… the fun stuff; the fun half. I left the songs about heroin and premature death in the cupboard.”

As luck would have it, his move into serious wagering inspired some changes in how he viewed his “monetised passion”, too.

“It taught me how to gamble, and I used that knowledge not by gambling on the horses or at a casino – I used that knowledge to gamble on my own career,” he says.

“So I’ve become my own promoter and my own manager, and I like to put my own money into things and back myself. I’m not frightened of taking my cash right down to the edge, and then waiting for the [concert] grosses to come in.

“My agent knows I don’t go for guarantees, I go for the door [earnings],” he says. “I like the door; I like the gamble. I’ve really taken charge of my business, and that’s worked so far. I might come a cropper with this country band.

“But that’s a gamble: you spend $70,000 on an album, and you want to make it back one day out of the touring, and I might not make that back until the fourth tour; I might break even ’til then. As long as you’re not exhausting your kitty, and you’re having fun – then keep punting.”

When Freedman sits at the piano to play a couple of songs for Review, he picks two from Kookaburra, which also appeared on Sancho: Man About a Dog and In The Last Life.

He’s been a generous conversationalist, but when the camera begins recording, he shifts gears into performer mode with the ease of a seasoned professional.

He plays and sings beautifully, despite describing the piano as “still the central mystery of my life”.

Of the instrument he began playing as a child, he says, “I wish I’d spent more time on it – but I didn’t. Then again, if I’d learned too much, I probably would have put more than four chords in No Aphrodisiac, and it wouldn’t have been a hit.”

As for the debut by The Whitlams Black Stump – which is completed by longtime Whitlams drummer Terepai Richmond, as well as highly regarded country musicians Matt Fell (bass), Rod McCormack (banjo/guitar) and Ollie Thorpe (pedal steel) – Freedman has laid out a blueprint for old fans and newcomers alike.

“If you’re familiar with our repertoire, you can see the joints in the carpentry of this album being put together,” he says. “There’s ‘catalogue’, which are hooks people know; there’s recent songs I’ve revisited, and there’s some covers written by friends, and the new song [Fallen Leaves].”

In his mind, an ideal listener is a country music fan who has no prior knowledge of these songs, even the Whitlams’ greatest hits.

“I hope that it fits together as an album to the country listener, who probably didn’t ever listen to Triple J,” he says.

“Hopefully those people in Deniliquin and Gunnedah will just hear a cohesive album. Time will tell.”

Earlier, on the drive in to Byron Bay, Freedman had stated he was imposing a two-drink limit on himself at dinner.

But after downing a couple of cold beers with Review while canvassing his past life on the punt, he decided to revisit the evening’s form guide, recalculate the odds, then make a new bet: one more, please.

The writer stayed at Barefoot at Broken Head as a guest of the artist.

Kookaburra is out now via E.G. Records. The Whitlams Black Stump’s tour continues in Tamworth, including Byron Bay Bluesfest, and ends in Avalon Beach, NSW (June 1 & 2). Tickets and details: thewhitlams.com