Dedicated to another lost friend, the band’s first album in 16 years marks a return to joyous form for the singer – after a four-year stint at the racetracks

Tim Freedman is happy, maybe even buoyant. “I’ve been enjoying writing and playing and singing more than I have in 15 years,” he says over a bowl of pasta. It’s day one of the publicity round for Sancho, the first album from the Whitlams in 16 years.

The jovial mood chimes somewhat with Freedman’s catalogue, which he admits is replete with “sad songs about blokes”. Usually sad songs about sad blokes – those who died, those who were left behind, those who wished they’d done more, done better.

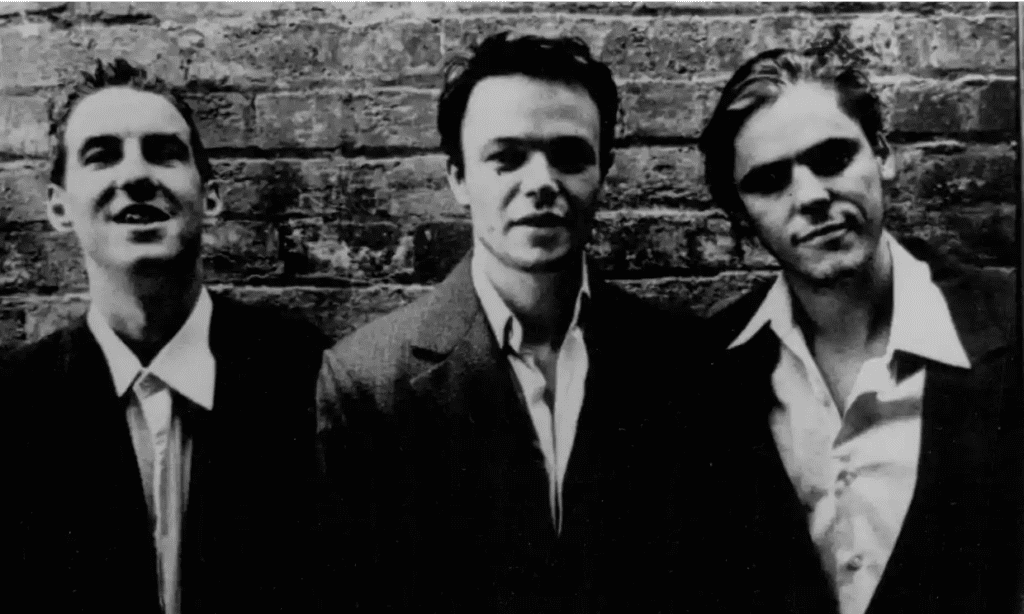

The Whitlams has been one of the most successful, genuinely independent bands in Australia for nigh on 30 years, but their full history can’t be told without reference to the deaths of two original members – Stevie Plunder (born Anthony Hayes) and Andy Lewis – and the troubled circumstances each suffered before they died.

The band’s 1997 breakthrough album Eternal Nightcap was dedicated to Plunder; his drinking and drug use had led to his departure from the band he co-founded, and he was found dead at the bottom of Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains in 1996. Meanwhile, Blow Up the Pokies – which addressed Lewis’ gambling addiction – was written by Freedman and Greta Gertler not long before Lewis’ suicide in 2000. Two years later, The Curse Stops Here saw Freedman determined to survive the loss of those friends and to do something meaningful with his own life.

Both songs became defining Whitlams tracks – but Freedman won’t accept that grief is his default setting. “I think the fellow in ‘I Make Hamburgers’ and ‘You Sound Like Louis Burdett’ and ‘Thank You (for loving me at my worst) – three of my most successful songs – are about being jocular and having a ball,” he says.

If any record could justify a set of sad songs about blokes it would be this new Whitlams album, which is named after and features two songs about longtime tour manager and live sound mixer Greg Weaver, who died suddenly of a heart attack in May 2019.

A constant in the Whitlams camp since Eternal Nightcap, Weaver was dubbed by Freedman: the Sancho to his “impractical, impetuous, disorderly” Don Quixote.

Quixotically, Sancho is anything but glum: the title track and Sancho In Love are filled with in-jokes, character assessments and a list of Weaver’s favourite things. They are packed with unalloyed joy and a sense of the world of a touring band and crew who lived in each other’s pockets for weeks or months or years on end.

“I’m not letting someone that wonderful go without putting down what we loved about him and the good times that we had. I was very conscious of not saying, ‘And now I’m sitting here feeling very sad’,” Freedman says.

“It was also a very different kind of death: it was random. He was a fellow who didn’t drink or smoke and it made no sense to anyone; it was a bowling ball from the left of centre. Also, it wasn’t just me dealing with that, it was the whole band.

“He was everyone’s friend [and] I allowed myself to be self-indulgent; I’m just gonna write this for the fellas, so we can all get together when it’s recorded and feel Greg in the room, dancing behind the desk. Which is a really fond memory.”

Nor is joy a stranger in the life of Freedman, a slightly grizzled 57-year-old with a teenage daughter and a steady relationship, who sports the lean, tanned, occasionally shaved look of a middle-aged surfer/philosopher, with the conversation to match.

“The easiest way to find meaning in life is to keep doing what you are actually quite good at and take a little bit of pleasure in occasionally being excellent,” Freedman says.

“Everyone from Socrates onward would say virtue is basically just trying to be good at something and applying your talents to it,” he says, explaining why he has dived back into music full-time.

“I do want to give joy with my music. There is no greater joy, and I forgot all about that for seven or eight years because I was a bit frazzled and I needed to find my enthusiasm.”

Nor is joy a stranger in the life of Freedman, a slightly grizzled 57-year-old with a teenage daughter and a steady relationship, who sports the lean, tanned, occasionally shaved look of a middle-aged surfer/philosopher, with the conversation to match.

“The easiest way to find meaning in life is to keep doing what you are actually quite good at and take a little bit of pleasure in occasionally being excellent,” Freedman says.

“Everyone from Socrates onward would say virtue is basically just trying to be good at something and applying your talents to it,” he says, explaining why he has dived back into music full-time.

“I do want to give joy with my music. There is no greater joy, and I forgot all about that for seven or eight years because I was a bit frazzled and I needed to find my enthusiasm.”

The persistent neck pain and cumulative effects of a decade of touring that built their following but wore them out, led to a short break that extended into eight years between national tours. But Freedman never closed the book on music entirely, playing occasional shows, solo and with the Whitlams. “I didn’t intend taking that long off; I stepped out of the room, and just didn’t step back in.”

But in a twist of perversity, he found that enthusiasm again while writing the song Sancho – just before Covid hit and wiped out much of the entertainment industry for two years.

“I wasn’t ambitious. But I’m actually ambitious now. I want to start doing more shows, bigger shows, better shows. I’ve got my energy back, my neck isn’t hurting after I had the operation, I can play the piano again without being in pain,” Freedman says. “When you have to take painkillers and champagne just to get onstage … it’s no way to meet your grandchildren.”

While music, champagne and painkillers took a step back, something else filled the void. Something hinted at on Sancho, an album dotted with small time crooks, gambling references and the language of the racetrack.

“In the time that I was having time off [from music] I was on the periphery of horse racing culture and to be honest, I was a full-time gambler for four years,” Freedman says. “I really enjoyed it because I could live at home and there was still this real adrenaline shot. Seventy minutes into a set at the Enmore Theatre is a very similar adrenaline to yelling ‘GO’ at the television when you are white-knuckling a favourite.

“I had a good time with the horses. I think one afternoon I won 300 grand, one Saturday afternoon. That took pressure off that year,” he adds, almost defensively. “Yeah, I was serious. But when you’re betting that much, it means you’re losing some Saturdays [too].”

Still, he won often enough for several major betting agencies to refuse to take his bets any more, he claims, preferring money from people more likely to lose consistently. “If you go close to making 3% on turnover, they don’t need you, because you’re not a loser. It’s just a hi-tech version of the pokies, it’s no different. You are allowed to win, it’s just not that common.”

It’s a counter-intuitive admission. Blow Up the Pokies was one of the Whitlams’ biggest hits, a furious lament against the industry that ruined his bandmate’s life. But Freedman is adamant that he was not, and is not, a gambler.

“I’ve never talked about it because I’m the guy who wrote Blow Up the Pokies, why would I be a gambler? Except I wasn’t losing,” he says seriously. “I had to stop in the end because you always stop when the quality of your data diminishes, and I’m not [an addictive] gambler. It’s like being in music for 20 years and not becoming an alcoholic – you should be able to bet professionally for three or four years and not become a gambler.

“It’s all about pushing your glass up against danger, then turning around and walking away.”

Sancho is out now. The Whitlams are touring Australia through February, March and April.

Bernard Zuel